When you sell your business, the purchase price is only part of the equation. What really matters is how much of that value you retain after the deal closes. And that often hinges on one word – Indemnification.

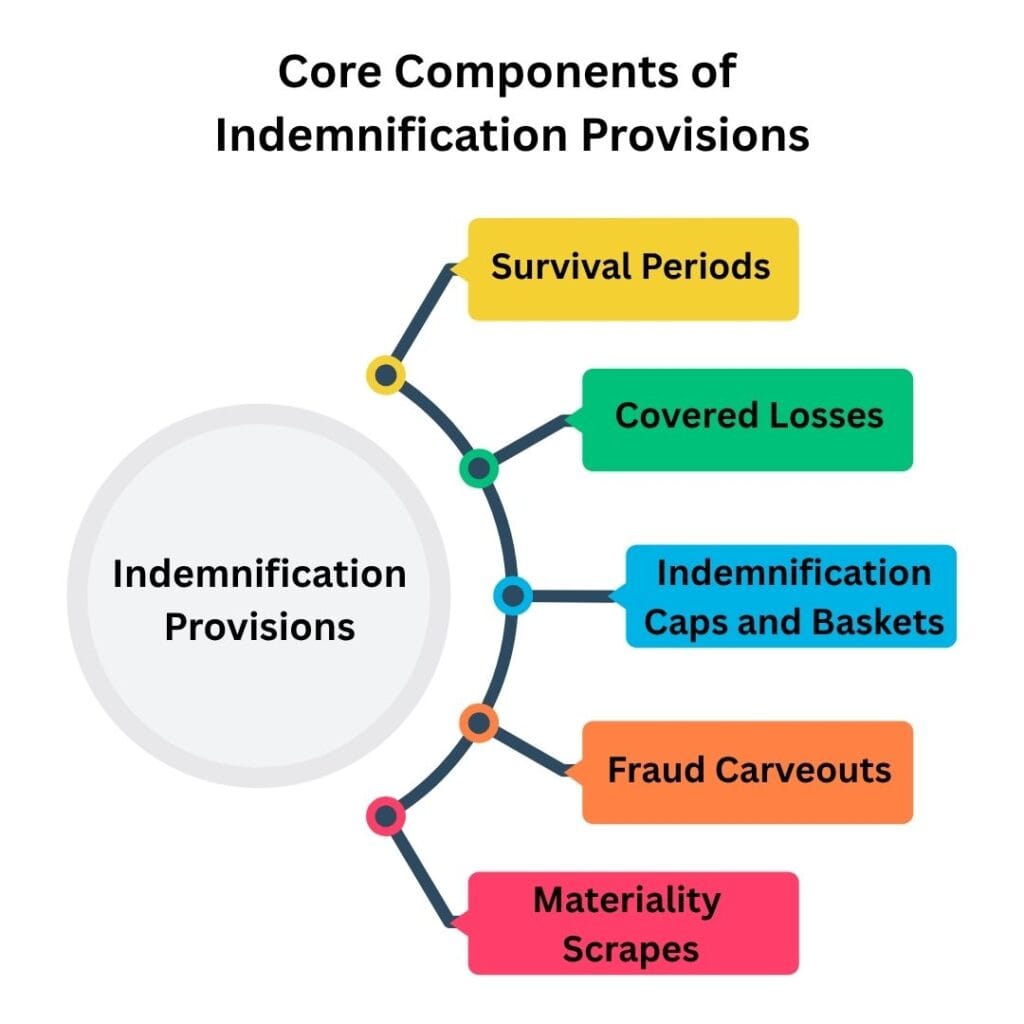

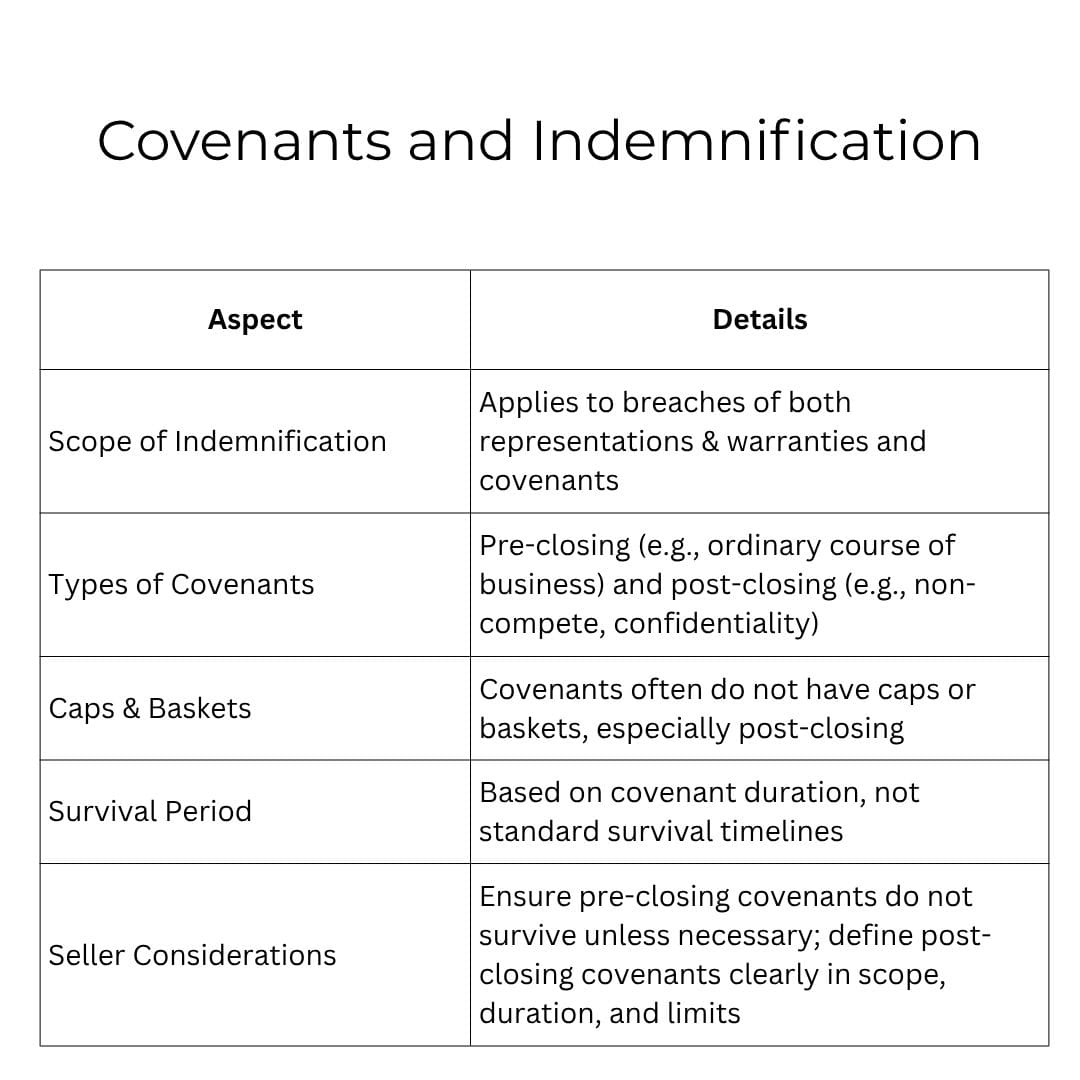

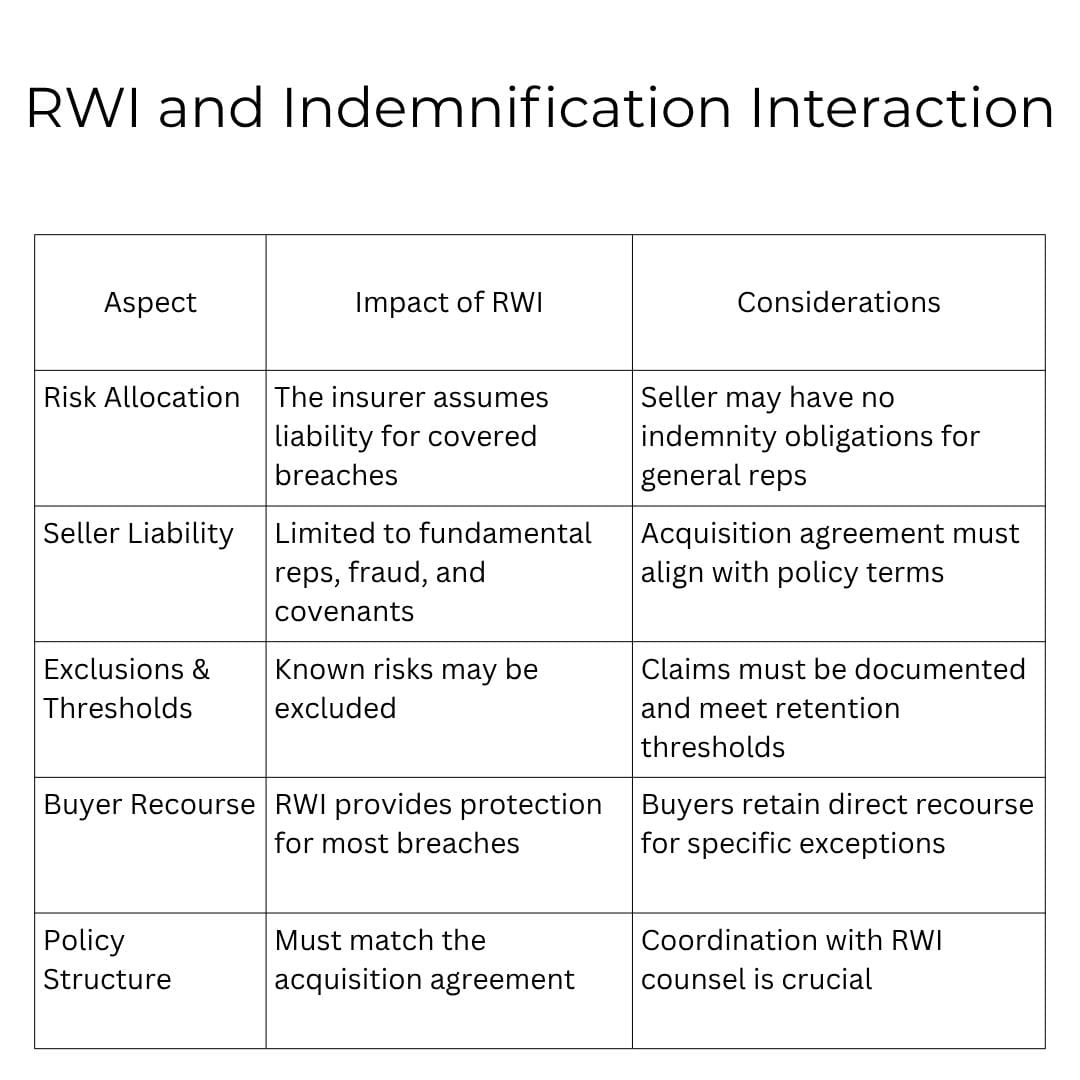

Often misunderstood or glossed over, indemnification provisions are one of the most consequential parts of any private company M&A transaction. They allocate post-closing risk, govern liability, and determine how claims are handled. For sellers, the wrong indemnification terms can quietly undermine the deal’s economics long after signing.

This page unpacks the core indemnification concepts and strategies that every seller should understand to protect their payout and mitigate lingering exposure after selling their business.